Cross-border M&A – Structuring and Key income-tax issues

- Background:

After having discussed the basic overview of key income-tax provisions relating to cross-border M&A in Part I, this article discusses key issues and some structuring options surrounding cross-border M&A.

- Key Issues in cross border M&A:

Since the cross-border M&A sphere is in a maturity phase, the tax and regulatory framework is also equally evolving. Based on the host of provisions provided in the IT Act, we have deliberated the income-tax implications for certain cross border M&A examples in Part I of the article. However, there are certain open-ended issues prevailing in the industry, and the ambiguity pertaining to the same has not been settled yet in the courts or is untested as of now. We have briefly discussed some of these issues from an Indian income-tax perspective, as under:

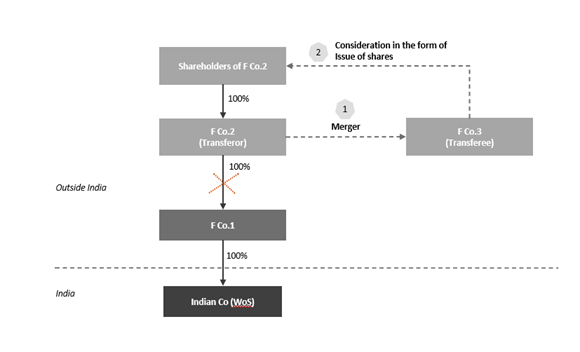

- Merger of F Co into F Co – No exemption to the shareholders:

Key Construct:

- F Co.2 to merge into F Co.3 (unrelated party), such that consideration is in the form of shares issued to the shareholders of F Co.2

- By virtue of such merger, F Co.2’s holding in the shares of F Co.1 shall stand transferred to F Co.3

- Income-tax implications in the hands of F Co 2 (transferor company):

If the said merger qualifies as an ‘amalgamation’ within the meaning of section 2(1B) for income-tax purposes; then the transfer of shares held in a foreign company deriving substantial value from India(i.e., the shares held in F Co.1 deriving value from the shares of Indian Co) by the foreign transferor company (F Co.2) to foreign transferee company (F Co.3) – may be exempt in the hands of such transferor (i.e., F Co.2) u/s 47(viab) provided the prescribed conditions are fulfilled.

- Income-tax implications in the hands of the shareholders of F Co.2

The provisions of the IT Act do not provide for any exemption to the shareholders of the transferor company, in a case of a merger of two foreign companies.

Hence, capital gains accruing on the transfer of shares held in F Co.2, may be taxable in India under the provisions of the IT Act, wherein such shares derive substantial value from India (i.e., in an indirect transfer scenario), except as covered within the small shareholders’ exemption[1].

One may also have to explore whether benefit under the treaty could be claimed in respect of such indirect transfer, depending upon aspects such as:

- the wordings of the respective treaties;

- the eligibility to claim treaty benefits; and

- the surrounding jurisprudence on the said aspect.

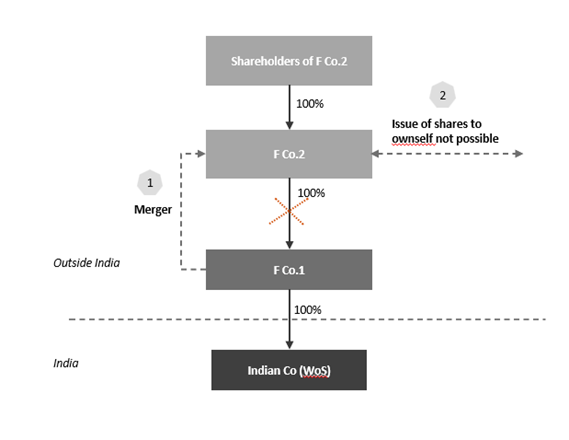

- Merger of F Co (WoS) into F Co (Parent):

Key Construct:

- F Co.1 (WoS) to merge into its Parent (F Co.2).

- As a consideration for such merger, transferee company (F Co.2) should issue shares to the shareholders of the transferor company (i.e., F Co.2 itself). In the present facts, F Co.2 cannot issue shares to own self.

- Income-tax implications in the hands of F Co 1 (transferor company):

If the aforesaid merger qualifies as an ‘amalgamation’ within the meaning of section 2(1B) for tax purposes; then one will have to analyze whether such an amalgamation of two foreign companies [where there is a transfer of shares held in an Indian Company (i.e., the shares held in I Co), by the foreign transferor company (F Co.1), to the foreign transferee company (F Co.2)] – qualifies for exemption u/s 47(via) of the IT Act ?

One of the key pre-requisite for such exemption is that:

- 25% of the shareholders of F Co.1 should continue to remain as shareholders of F Co.2

In the definition of ‘amalgamation’ u/s 2(1B) and in the exemption provided u/s 47(vii) in case of mergers where the transferee company is an Indian Company – an exception has been provided for a situation where the transferee company itself is the shareholder. A similar exception is absent in the language of section 47(via) where the merger is of two foreign companies.

In the present facts, no shares have been issued as consideration, as the transferee company itself is the shareholder. Consequently, an ambiguity arises that in absence of exception clause in section 47(via), whether the condition of “continuity of 25% of the shareholders” stands fulfilled in the current scenario.

One will have to thus evaluate basis first principles as under:

- Even though the law prescribes the requirement of “continuity of 25% of the shareholders”, such conditionality could not be fulfilled in the present facts because of “impossibility of performance” at F Co.2’s level;

One may argue that it is “impossible” for F Co.2 to issue shares to own self, i.e., impossible to perform the issuance of shares and satisfy the conditionality provided u/s 47(via).

- Income-tax implications in the hands of the F Co.2 (as “shareholders of F Co.1”):

As mentioned earlier, there has been no exemption u/s 47 for the shareholders, in the scenario of a merger of two foreign companies. Hence, evaluation based on first principles would be needed for the capital gains accruing in the hands of F Co.2, on the transfer of F Co.1’s shares which derive substantial value in India – refer to the probable arguments as provided for the shareholders under paragraph 3.3 of Part I of the article.

Practically, after the merger is completed, the Indian operations of the transferor company could be carried out by the surviving foreign entity, either directly or through a branch in India. Consequently, there is a significant risk that the tax authorities may characterize the India presence of the surviving foreign entity as constituting a PE in India.

For example, where an Indian amalgamating company is engaged in an asset intensive business viz a manufacturing plant in India; then post the outbound merger with foreign amalgamated company, the Indian manufacturing plant shall be regarded as a ‘branch office’ of a foreign company in India and thereby regarded as a PE in India for tax purposes.

Consequently, the aforesaid PE risk may result in ‘business profits’ earned by the surviving foreign entity (from its operations in India being taxed in India) at a higher rate of 40% (exclusive of the applicable surcharge and cess). Hence, one will have to explore the structuring of the Indian (post-merger) operations in a manner that lowers the risk of PE exposure.

- Dividend re-characterization risk in an inbound merger of foreign WoS into Indian parent:

In a scenario where a foreign subsidiary (transferor company) having surplus reserves, has amalgamated into its Indian parent company (transferee company); the tax authorities may possibly allege that the transfer of assets by the transferor company is nothing but the distribution of such free reserves by the company to its shareholder.

Accordingly, there is a possibility that the tax authorities may characterize such distribution as in the nature of ‘dividend’ and thus proceed to tax the same in the hands of the recepient shareholder.

On this matter, one may explore the argument provided under the CBDT Circular dated 09-10-1967 – an extract of such circular states as under:

“…. The Board, are, therefore, of the view that the provisions of sub-clause (a) or (c) of section 2(22) are not attracted in a case where a company merges with another company in a scheme of amalgamation”

Based on the ratio laid down by the aforesaid circular, one may possibly contend that any transfer of assets including the transfer of accumulated profits embedded in such assets; ought not attract the taxability as ‘dividend’ provided within the meaning of section 2(22)(a) or section 2(22(c) of the IT Act.

- Internalization:

Due to favorability of India in the world economy and with the increasing appeal of the Gujrat’s GIFT City in India, many overseas companies are now making a ‘strategic move’ towards India. This brings in the concept of ‘internalization of businesses into India’.

This trend of internalization is being largely adopted by Indian start-ups (who had originally relocated their holding company to overseas jurisdictions by way of ‘flipping’) – are now opting to “reverse flip back into India” i.e., move their bases back into India, due to several factors such as:

- favorable economic policies/government incentives and the easing of regulations in India;

- significant untapped pool of domestic retail investors eager to invest;

- burgeoning domestic market;

- growing investor confidence in the country’s start-up ecosystem; and

- Eyeing for a public listing in Indian markets, etc.

Hence, various restructuring exercises (such as share swaps or mergers, etc.) are being adopted by start-up companies, in order to tweak their corporate structure and thus enable the relocation of their holding company and intellectual properties, back into India.

Headlines for various start-ups which have done or contemplating their “flip back” or locally known as “Ghar Vapsi” into India, are in the news. In light of the above background, we have briefly touched upon some of the structuring routes by which internalization could be ideated as well as the key income-tax issues surrounding such structures:

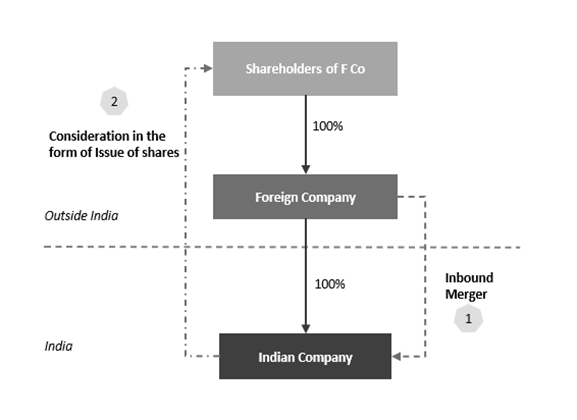

- Inbound merger of a Foreign Company into an Indian Company:

Inbound merger is the most basic type of an Internalization structure, wherein the overseas shareholders get control in the Indian Company and the Indian Company receives the business directly from the Foreign Company. Such strcuture is best suited where legal and the regulatory framework of the overseas jurisdiction (where the Foreign Company is situated) permits[2] such outbound mergers.

Key Construct:

- Merger of F Co (transferor company) into I Co (transferee company);

- Issuance of shares as a consideration for such merger, to the shareholders of F Co.

Key income-tax considerations:

- If the said merger qualifies as an ‘amalgamation’ for income-tax purposes and since the transferee is an Indian Company; exemption u/s 47(vi) and 47(vii) may be provided to F Co and the shareholders of F Co, respectively.

- One should note that the aforesaid structuring by way of ‘inbound merger’ is the simplest option for carrying out internalization. However, as mentioned; if the overseas jurisdictions do not[3] permit outbound merger for F Co, then other options for ideating internalization have been discussed below in the ensuing paragraphs.

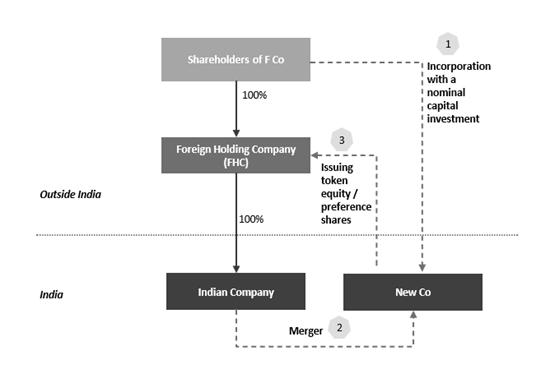

- Merger into mirror entity:

Mirroring the overseas shareholding pattern at Indian level, is also one of the types of Internalization structures, wherein the Indian Company’s business gets transferred to a New Company which is then directly controlled by the overseas shareholders.

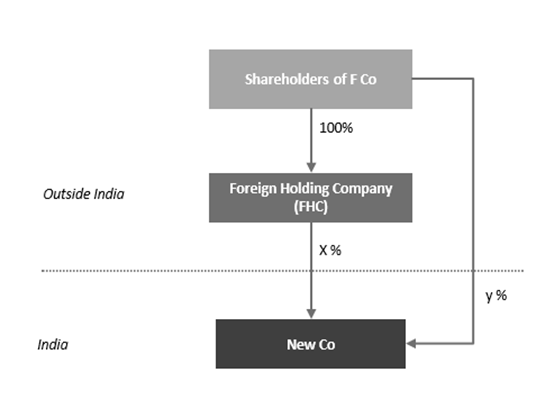

Proposed Structuring:

Key Construct:

- Shareholders of FHC will form a New Co. in India, with mirror (identical) shareholding pattern of FHC;

- Merger of India Co. (transferor company) into New Co. (transferee company).

- As a consideration of such merger, issuance of nominal equity shares to FHC (shareholders of transferor company), by New Co.

Resultant Structure:

Construct achieved:

- FHC obtain the Indian business by way of ownership in New Co and the shareholders of F Co also achieve control in New Co. in India.

- Shareholders of F Co have obtained a direct control in the Indian business, without carrying out any cross-border merger[4]

Key income-tax issues / considerations:

- Whether the transaction of merger shall qualify as an ‘amalgamation’ within the meaning of section 2(1B) for tax purposes; given that nominal shares are issued as a consideration for the amalgamation

- Whether the issuance of nominal shares, trigger the applicability of section 56(2)(viib)[5], in the hands of New Co. (i.e., transferee company issuing shares upon merger)

- Considerations around the cost of acquisition and the period of Holding of the shares acquired in New Co., by way of:

- Subscription (by the shareholders of FHC); and

- Pursuant to amalgamation (by FHC)

- Potential risk of GAAR exposure, for which strong commercial rationales may be built to substantiate to the tax authorities.

- Considerations surrounding the migration of ESOPs from FHC to I Co.

- Realignment of business operations/business model, between FHC and I Co.

- In addition to the aforesaid option of “merger with mirror entity” under paragraph 3.2 above, one may also explore other options for internalization such as:

- merger into mirror entity, after the slump sale;

- Swap of shares;

- Liquidation of FHC; and

- In-specie distribution of the shares of I Co., by FHC; etc.

- Externalization:

With the intent of globalization, businesses are now expanding beyond their jurisdiction, and India is no exception. The last decade has witnessed an upsurge of Indian companies expanding globally and tapping their potential in the foreign markets. This brings in the concept of ‘Externalization’ wherein Indian companies are “flipping their businesses outside India” with flexibility to list shares overseas.

Externalization involves:

- migration and mirroring of cap table from existing Indian company to the Overseas Holding Company (‘OHC’); and

- subsequent realignment / consolidation of India business under the OHC structure.

In light of the above background, we have briefly touched upon some of the structuring routes[6] by which externalization could be ideated as well as the key income-tax issues surrounding such structures:

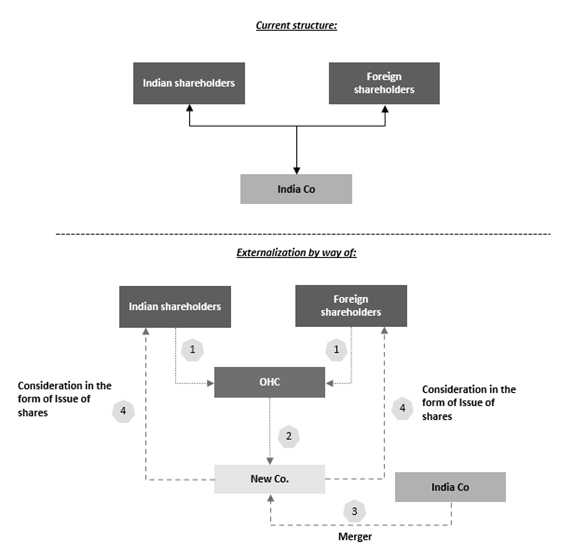

- Merger:

Mechanics:

- An overseas holding company (‘OHC’) to be incorporated by Indian shareholders and the foreign shareholders – thinly capitalized. Shareholding in OHC to be in ratio similar to India Co., i.e., mirror shareholding.

- OHC to incorporate New Co. in India as a 100% WoS.

- India Co to merge with New Co.

- In consideration of such merger, New Co to issue nominal equity shares, to the Indian and foreign shareholders (being the ‘the shareholders of the transferor company’).

Key income-tax issues / considerations: similar to as discussed under paragraph 3.2 above.

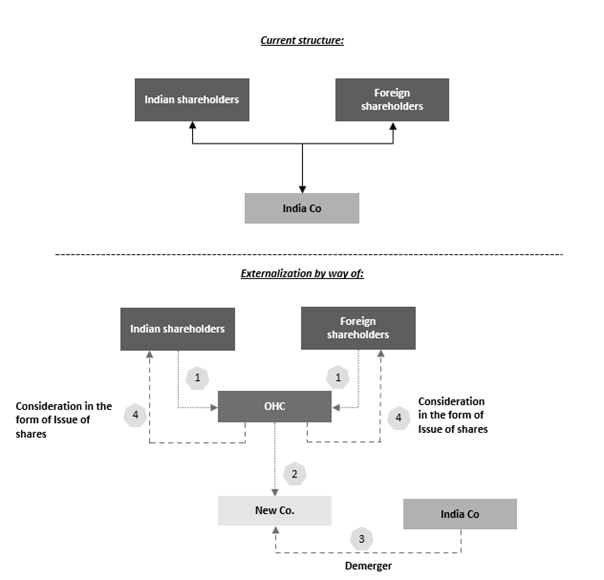

- Demerger:

Mechanics:

- OHC to be incorporated by Indian shareholders and the foreign shareholders – thinly capitalized. Shareholding in OHC to be in ratio similar to India Co., i.e., mirror shareholding

- OHC to incorporate New Co. in India as its WoS.

- Substantially the entire business of India Co (‘Demerged Company’) to be demerged into the New Co.

- In consideration of such Demerger, OHC (the wholly-owned shareholder of New Co) to issues its own shares to the Indian and foreign shareholders (being the ‘shareholders of Demerged Company’).

Key income-tax issues / considerations:

- Who shall qualify as a ‘resulting company’ within the definition of section 2(41A) of the IT Act:

- OHC (the company who has issued the shares upon demerger); or

- New Co. (the company to whom the business of the demerged undertaking has been vested upon, pursuant to the demerger)

- Due to the involvement of two such resulting companies, the impact on the tax neutrality of such demerger u/s 47(vib).

- Concluding remarks:

Striking a cross-border deal requires profound forethought to facilitate smooth and seamless implementation of such transaction across two jurisdictions, across two businesses and also in line with the sentiments, cultures of the people working in the organizations involved. The transaction structure needs to be tax-efficient and compliant with a host of regulations (local and overseas); and at the same time also meet the commercial desires of the parties involved. Regulatory and corporate laws play a key role in ensuring that a cross-border transaction is consummated in a conducive manner; whereas taxation plays a key role in striking the equilibrium between cost v/s benefit and thereby gauge the various outflows and adverse consequences involved (if any). However, as we have discussed in this article; taxation remains a vexed issue and hence various income-tax aspects are still open, ambiguous and eyeing clarity from law.

[1] Indirect transfer tax shall not be applicable for small-scale investors who either individually or with their related parties (at any time within 12 months preceding the date of transfer):

- do not hold more than 5% of the total voting power or share capital or interest in the foreign entity that holds Indian asset; and

- do not hold any right of management or control in the foreign entity that holds an Indian asset;

[2] Based on desktop research, some of such jurisdictions (permissible ones) are – Mauritius, Luxembourg

[3] Based on desktop research, some of such jurisdictions (non-permissible ones) are – UAE, Japan, Australia, Canada, Singapore, Hong Kong

[4] The shareholders of F Co would have obtained a direct control in India Co, if FHC would have merged into India Co (i.e., inbound merger for India, and outbound merger for FHC). However, if outbound merger is non-permissible for FHC, then the structuring for internalization could be explored in the above manner i.e., by merging of two Indian companies and subsequently obtaining control in the transferee company.

[5] where an closely held company receives any consideration from any person for the issue of shares in excess of the fair market value [FMV as determined under Rule 11UA(2)]; such excess amount of ‘premium’ shall be chargeable to tax under the head ‘Income from Other Sources’ in the hands of such issuer company

[6] The existing article/ paragraphs do not discuss the recent proposals/ amendments under FEMA and Company law, involving direct listing of Indian companies on international stock exchanges in IFSC